The Declaration of Duty

How Jefferson's Assertion of Universal Rights was the Beginning of America's Global Wars

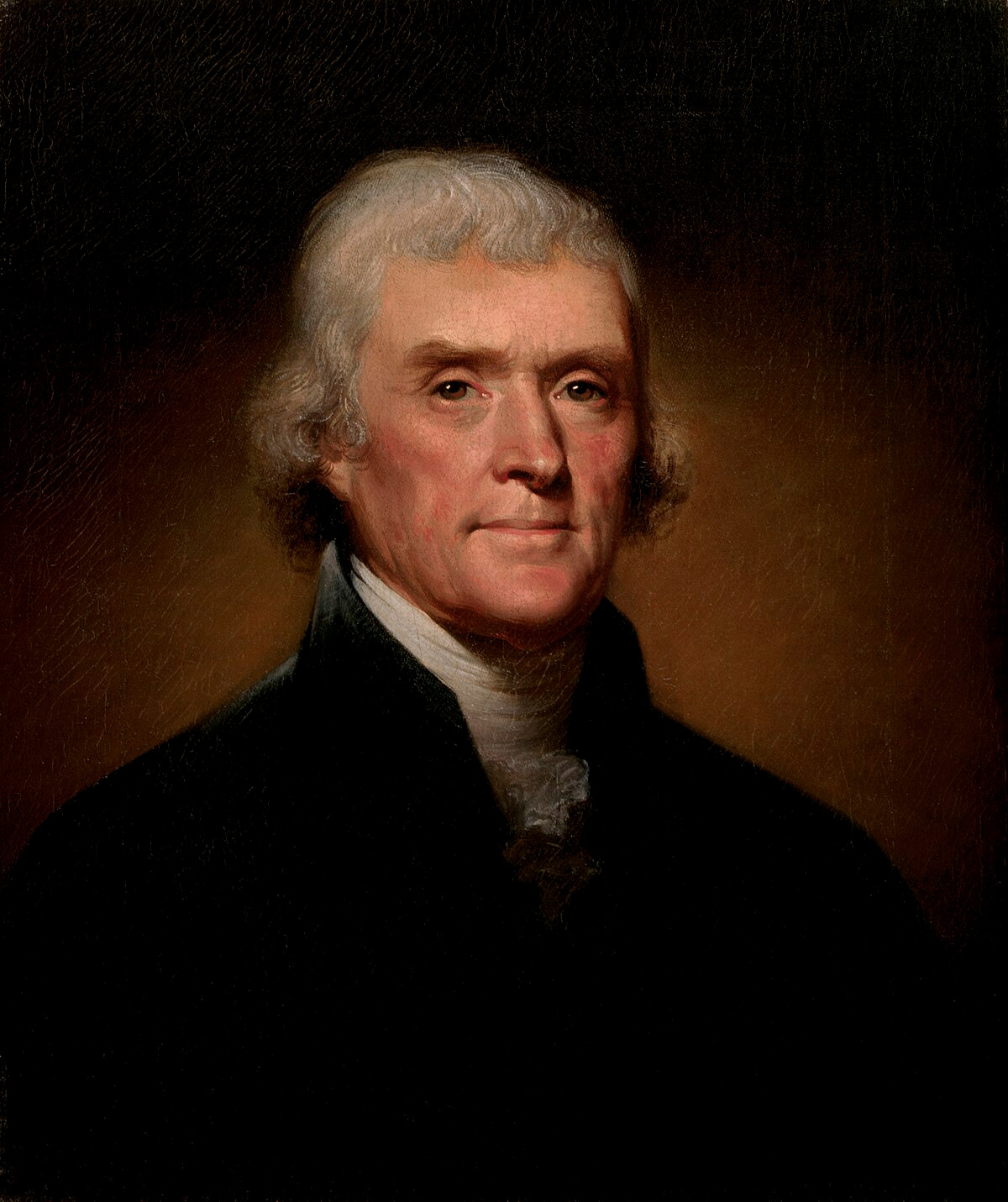

Feeling the “excessive heats of the city coming on fast,” when Thomas Jefferson arrived in Philadelphia in May of 1776 to attend the second meeting of the Continental Congress, he moved into lodgings “in the skirts of the town” a quarter mile to the west of the State House where the delegates would convene. There, he would have “the benefit of a freely circulating air” in which to read, think, and write. The air on the west side of town was also free of the noise emanating from the taverns that filled central Philadelphia. Most of the city’s 160 taverns were concentrated in the half-mile square area to the east of the State House at Sixth and Chestnut Streets. Many were lower-class establishments catering to a mix of Irish laborers and free blacks who were known for their raucous singing, shouting, cursing, jesting, drumming, fiddling, and dancing. Jefferson occupied a two-room flat on the second floor of a newly built brick house at Seventh and Market Streets, several blocks from the nearest disorderly tavern and well above any human activity on the street below. The parlor room, where he would spend most of his time, contained a writing desk and a clock. It was an ideal place for a man of the mind to work.

Whether Jefferson and the signers of the Declaration of Independence intended the founding words of the nation to be an injunction to forever expand it as an empire, the men who determined the major foreign policies of the early United States certainly behaved as if they did.

In June, Jefferson was appointed to a committee, along with Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Robert Livingston and Roger Sherman, charged with producing a document that would justify the severing of ties to Britain.

At his desk, above the street and away from the people, Jefferson began writing the first draft. Though his task was immediate and specific—to explain why Americans should separate from Britain on July 4, 1776—what first came from Jefferson’s pen were claims about all people, everywhere and forever:

When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

The next sentence was an assertion of the existence of rules that were universal, eternal, and written in nature.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

This passage is famous both for its radical egalitarianism in a time when hereditary monarchs and masters ruled the world and for its implicit hypocrisy given the radical inequality between Jefferson and the men he owned. But it should also be famous for its mysticism and megalomania. Jefferson and his co-authors presumed to speak not just for Americans, only a fraction of whom they could claim to represent, but for all of humanity and for God. The Founders were self-proclaimed members of the philosophical movement that came to be known as the Enlightenment, committed to rationality over faith and science over superstition. Yet they presented their doctrine of natural rights without even an allusion to rational argumentation or scientific evidence. It is an unverifiable and unsupported claim that applies to men the Founding Fathers could only have known as abstractions. The founding idea of the United States of America is an article of faith.

The third sentence asserts the right of revolution, often considered to be a radical and liberatory claim regardless of its foundation in metaphysical belief:

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. . . .

But who are “the People” and which governments do they have the right to overthrow? If a foreign government is destructive of life, liberty, and happiness in a land they do not inhabit, do men like the authors of the Declaration of Independence have the right—or the duty—to take it upon themselves to alter or abolish it? The next two sentences, which are rarely discussed, suggest just such an imperial duty:

Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

The “people” do not have the right to live with evil. If they choose not to abolish the evil they themselves suffer, is it not the duty of prudent men to abolish it for them?

Whether Jefferson and the signers of the Declaration of Independence intended the founding words of the nation to be an injunction to forever expand it as an empire, the men who determined the major foreign policies of the early United States certainly behaved as if they did.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thaddeus Russell to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.